Windship 2.0 – Shipping of tomorrow

The main motivation for Ron de Vos to design windships is that he wants to do his bit to manage the risk of climate change. Sixteen designs have now been compiled in a book.

The IMO (International Maritime Organisation) is calling for urgent action to reduce climate change and its effects. The IMO’s greenhouse gas strategy includes an ambition to reduce,greenhouse gases to ZERO by or around 2050. An interim requirement of a 40% reduction by around 2030 was formulated recently.

The idea to design a sailing cargo ship arose while writing the book Dutch frigates and barques (2013) on the technical development of a sailing cargo ship in the nineteenth century. Ron de Vos digitised more than a hundred historical sail and line plans. One of these was the Kosmopoliet III, a Dutch freighter designed by C. Gips, Dordrecht. Would it be possible to improve this ship with modern insights and with modern equipment?

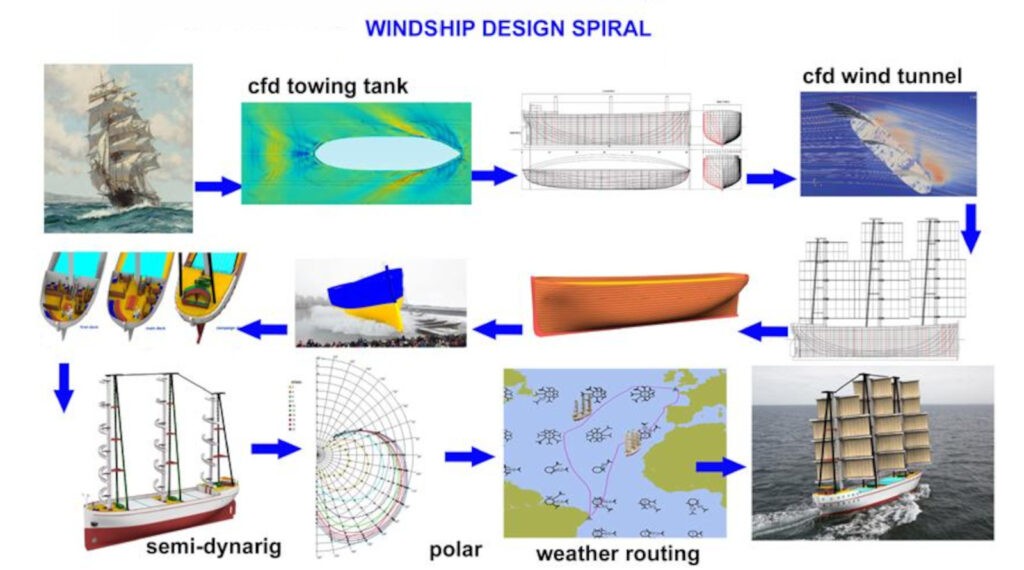

Thus was born the first ship: Windship I. Fifteen new preliminary designs followed, ranging from 350 to 30,000 tonnes. The hulls are very different. The basis of the sail plan came from German Wilhelm Prölß, who developed the DynaRig. De Vos then came across a study by John B. Woodward et al., from the University of Michigan, commissioned by the US Maritime Administration. Woodward came up with the idea of a semi DynaRig. This rig de Vos further developed into Ron’s Rig.

Ron de Vos, Windships 2.0 Shipping of tomorrow

Price 47.50 , to be ordered at www.windschip.nl

Editorial comment

In the book Windships 2.0 Shipping of tomorrow, author and designer Ron de Vos shows how he got from the first 34-metre-long design – a coaster – to the 190-metre-long ‘Windgigant’. The 16 ships in the book are described with drawings, technical data and a text about the purpose of each ship.

Despite Ron’s long-standing advocacy of contemporary sailing cargo shipping, it remains unfortunate that his stance could not yet be tested in practice. Of course, the rigging has already been tested: aboard the sailing cruise ship ‘Maltese Falcon’. However, after reading the impressive dossier, questions remain.

Building on the tradition of ship designs of the past, while giving results that have been tested in practical sailing, lacks the knowledge developed in designing modern sailing superyachts. Would a Windship sail higher upwind with a modern underwater hull? Some of the routes described do require it. Let’s take another look at the time-honoured ‘Ocean Passages for the World’.

The route from the Netherlands to New York suffers from westerly winds in the English Channel and goes via the Canary Islands along the trade wind that avoids the Azores high. The great circle route ‘around the north’ is much shorter, but has headwinds and ice conditions. Routing becomes of great importance for sailing merchant shipping. A number of charts in the book raise quite a few questions regarding routing. In the old sailing days, the Doldrums were notorious, and it is unlikely that a modern sailing captain would want to sail into a dead calm.

One of the most interesting ships is undoubtedly the largest Windship; the Wind Giant. Using lots of solar cells and a propeller shaft generator, the ship can make hydrogen. The ship will sail until its hydrogen tanks are full and disembark its cargo in a port or with other hydrogen-fuelled ships. A sailing green power plant; a contemporary Flying Dutchman, roaming the oceans, in search of wind to make green power.

Ron de Vos shows in this book ‘how it can be done’, for which all credit is due. Hopefully a Dutch shipyard will once make his dream come true.